By Gary Cokins, Global Product Marketing Manager, SAS Institute Inc.

Organizations increasingly want to better understand their revenues and

costs and, in particular, the behavior of factors that drive these top and

middle lines of the bottom-line profit equation. The reason for increased

interest in more detail is obvious: The margin for decision error is getting

slimmer. Mistakes in poor product selection, wrong channel options, or improper

customer targeting can no longer be offset by good choices made elsewhere in a

business.

What questions might managers and employee teams ask about their customers that

can be answered with detailed profitability reporting? Here are some examples:

- Do we push for volume or for margin with a specific customer?

- Are there ways to improve profitability by altering the way we package,

sell, deliver or generally serve different types of customers?

- Does the customer’s sales volume justify the discounts, rebates or

promotion structure we provide to that customer?

- Which products are relatively more profitable to cross-sell or up-sell?

- Can we realize the benefits from our changing strategies by influencing

our customers to alter their behavior to buy differently (and more

profitably) from us?

- Can we shift work to or from some of our suppliers based on who is more

capable or already has a superior cost structure compared with ours?

Risks from Inaccurate Cost Calculations

Companies plan and control their operations using accounting information that is

assumed to accurately reflect the costs of their products and standard service

lines. In fact, this is often not the case. The recorded expenses, such as

salaries and supplies, may be exact in their amounts because they are externally

audited and automated accounting systems capture them – but the problem is then

transforming those expenses into their calculated costs of the business

processes and the products that in turn consume those process costs.

The costing systems of many companies, with their aggregated summaries and their

broad averaging allocation of indirect costs, mask reality with an illusion of

precision. In fact, traditional cost systems typically provide misleading

information to decision makers with minimal transparency to understand what

constitutes a product’s cost. Companies that apply activity-based costing (ABC)

principles and their supporting software systems resolve the cost distorting

error of allocating expenses using broad averages (e.g., number of units

produced, sales amount, or labor input time). These cost allocations violate the

accounting principle of a cause-and-effect relation to transform consumed

expenses into calculated costs. ABC replaces broad averages with quantified

activity cost drivers that trace each work activity (at a reasonable level of

disaggregation) to the type of output, product or standard service-line that

causes and consumes the work activity.

To further complicate matters, with the shift in attention from products to

customer services, managers are also seeking granular ‘costs to serve’

customer-related information. These are not all the costs related to making a

product or delivering a standard service line (e.g., a bank checking account),

but rather they are the costs from interactions with customers, such as a help

desk call. The problem with accounting’s traditional gross profit margin

reporting (i.e., restricted to only product cost profit margins) is managers

cannot see the bottom half of the total picture – all the profit margin layers

eroded from distribution, selling, credit, payments, and marketing costs.

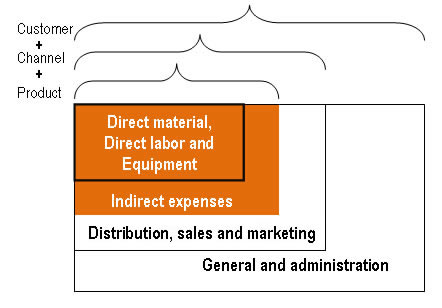

Exhibit 30.1 illustrates an organization’s entire expenses. The product and

standard service-line costs are in the shaded area. The concern here is tracing

the non-shaded area costs to types of channels and customers.

Exhibit 1. Costs from Sales and Marketing Are Not Product Costs

The unacceptable result of not converting these types of expenses into

customer-related costs is that executives, managers, and employee teams receive

incomplete profit reporting that is not segmented by customer; and the product

profitability data they do receive is flawed and misleading. They deserve fully

loaded cost and profit reporting that encompasses all the traceable expenses of

their end-to-end value stream costs–from supplier-related purchasing to customer

service. How can recent advances in managerial accounting methods and technology

deploy the vast potential that companies have from their business intelligence

systems?

Costs Need to be Causally Traced, Not Allocated on Broad Averages

Businesses with thousands of customers want to scale-up their cost and profit

reporting and visibility at the individual customer level, but their costing

systems cannot accomplish this. As a result, organizations lack the essential

information for making much better decisions about product mix, customer mix,

marketing, channel strategies and sales programs.

To better analyze revenue, cost and the resulting profit margin information,

businesses need to be able to define segmented reports on the fly. This includes

tracking profit for different time periods by individual customers, by

individual products and by specific sales channels, distribution channels,

branches, service centers, or sales outlets. To enhance the identification and

investigation of problems, organizations also need the flexibility of

at-a-glance and drill-down views to see costs and profits with fine granularity.

ABC systems are designed to produce profit and loss income statements for

customer segments and if needed for individual customers. With ABC product and

service-line related work activity costs are layered into each product and

service line. In addition cost-to-serve related work activity costs are

additionally layered into each channel and customer. The volume and mix of

products, service lines, and channel costs that each customer consumes is also

layered in.

Accountants rarely isolate and directly charge customer-related activity costs

to the specific customer segments causing these costs. As a result, in financial

accounting terms, the costs for selling, advertising, marketing, logistics,

warehousing and distribution are immediately charged to the time period in which

they occur. Accountants refer to these as period costs. But classifying expenses

that way is for external financial accounting for banks, investors, and

regulatory agencies. What we are discussing here is internal managerial

accounting to support the analysis and decision making of managers and employee

teams. The accountants must begin applying the same costing principles for

product costing, typically ABC principles, to types of channels and types of

customers so that there is visibility to all traceable and assignable costs.

Otherwise, you have no clue where you are making and losing money.

The problem is the accountants are not tasked to trace them to channels or

customer segments. But today’s selling, merchandising and distribution costs are

no longer trivial costs – they are sizable. There should be a focus on the

customer contribution margin devoid of simplistic and arbitrary cost

allocations. Companies with goals of sales growth at any cost need to temper

their plans with a goal of profitable sales growth.

In the end, services will be added to products, and unique services will be

tailored for individual customers. Activity-based costing data will be essential

to validate and prioritize the financial merits of which services to add and for

which customers.

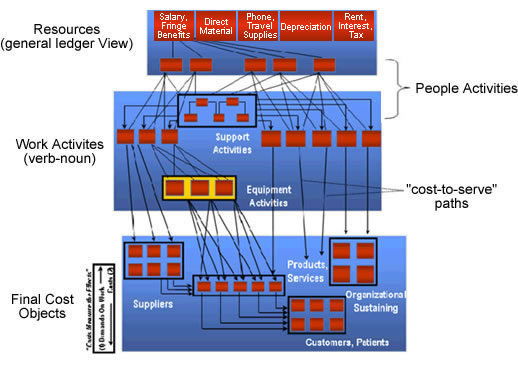

ABC resolves the costing accuracy problem with its rational cause-and-effect

cost tracing logic. It complies with accounting’s causality principle. ABC

transforms each department’s expenses as captured in the general ledger

accounting system into its calculated costs of work activities (that belong to

business processes) and ultimately into its products, service lines, channels

and customers.

Exhibit 2 illustrates an organization’s enterprise-wide expense structure

flowing into the ultimate final costs of its end-customers and its

organizational sustaining cost (i.e., those expenses transformed into work

activity costs that are not caused or traceable to products or customers).

Exhibit 2. Activity-Based Cost/Management Cost Assignment Network

Equipped with a costing methodology that correctly models the consumption of

resources base on accounting’s causality principle, one can rely on its

information to be valid for reliable analysis, control, planning and decision

support.

What Is Needed Is a Profit and Loss Statement for Each Customer

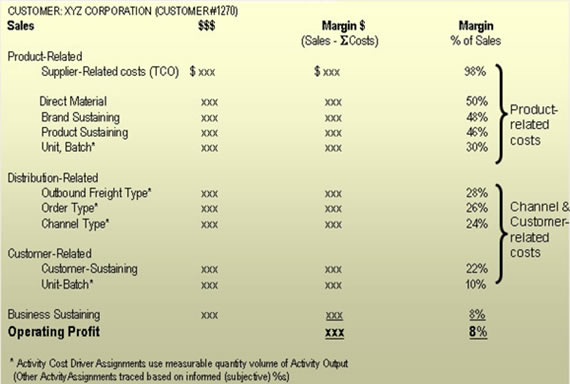

Exhibit 3 illustrates the individual customer profitability statement that is

the result of these cost layers. Using ABC, there can now be a valid profit and

loss (P&L) statement for each customer as well as logical segments or groupings

of customers. A tremendous amount of detail lies below and within each of these

reports. For example, the individual products and service lines purchased can be

examined in greater detail; they comprise a mix of high and low margins based on

their own unit costs and prices. In other words, in a customer-specific P&L

summary, the product or service line is reported as a composite average, but

details about the mix are viewable. In addition, within each product or service

line, the user can further drill down to examine the content and cost of the

work activities and materials for each product and standard service line.

Exhibit 3. Customer Profit and Loss Statement

ABC users refer to this data mining and navigating as ‘multidimensional

reporting;’ and they use the online analytical processing (OLAP) software tools

for viewing the output of the ABC calculation engine. This is powerful

information. The sum of all the customer P&L statements for this type of report

will be the entire business’s enterprise-wide profit (or loss). That is, it can

be reconciled with the company’s official books: Its total spending and the

resulting ‘bottom line.’

Performance management systems combine ABC information with planning and

performance measure and alignment tools; but what makes performance management

so appealing is that it is work-centric. The foundation for performance

management is built on what people and equipment do, how much they do it, and

why.

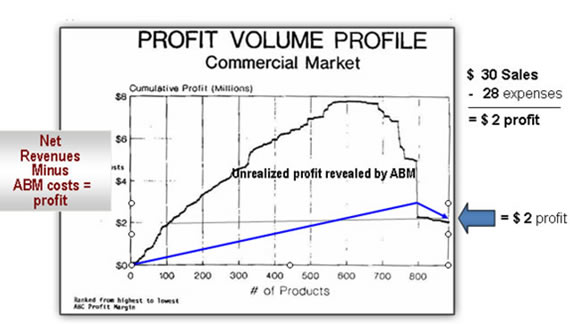

With valid cost modeling, Exhibit 4 displays a graph line at the top – referred

to as the ‘profit cliff’ of the true cumulative build up of each product’s

profit rank ordered from the most profitable to the least (often products at a

financial loss where their costs exceed their revenues). The graph illustrates

how unrealized profits can be hidden due to inadequate costing methods. The

accountants are not properly assigning the expenditures based on the causality

principle of accounting. The graph is of each product’s cost, net of sales, to

reveal each product’s and service line’s profit.

Exhibit 4. Cumulative Profit Distribution by Product

The products are rank-sorted left-to-right from the largest to the smallest

profit margin rate. The very last data point equals the firm’s total net profit,

as reported in its profit and loss (P&L) statement. For this organization, total

revenues were $20 million with total expenses of $18 million, to net a $2

million profit, but the graph reveals the distribution of the mix of that $2

million net profit. Although not empirically tested, experiences with these

measures show that the total amount of the profits, excluding any losses,

usually exceeds 200% of the resulting reported net profit; greater than 1000%

has even been measured.

ABC information is typically shocking to executives and managers since their

prior belief from their traditional broadly averaged costing method is the flat

graph line at the bottom with the small decline where each product’s cost was

distorted. This graph line has its accuracy removed by the broad-brush averaging

of traditional cost allocations rather than tracing and assigning each activity

cost using its proportionate activity cost driver.

Migrating Customers to Higher Profitability

What does all this information reveal? First, it quantifies what everyone may

already have suspected: All customers are not the same. Some customers may be

more or less profitable based strictly on how demanding their behavior is.

Although customer satisfaction is important, a longer-term goal is to increase

customer and corporate profitably. There must always be a balance between

managing the level of customer service to earn customer satisfaction and what

the impact from doing that will have on shareholder wealth. The best solution is

to increase customer satisfaction profitably. Because increasingly more

customers will expect and demand customization rather than standard products,

services, and orders, understanding this balance will be important.

ABC data facilitate discussions about arriving at that balance. Many managers

are unwilling to take any actions until presented with the facts.

In the company P&L in Exhibit 3, there are two major ‘layers’ of contribution

margin:

1. By mix of products and service lines purchased

2. By ‘costs-to-serve’ apart from the unique mix of products and service lines

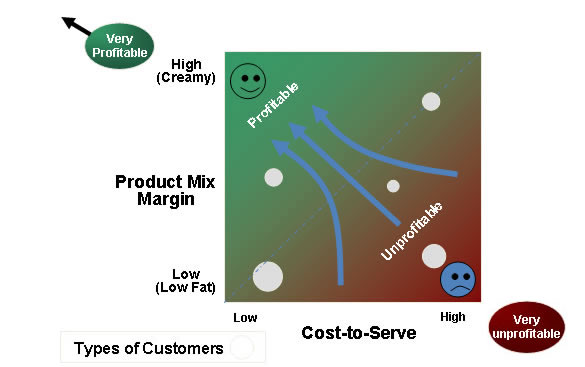

Figure 5 combines these two layers. Any single customer (or cluster) can be

located as an intersection. Figure 5 provides a two-axis view of customers with

regard to the two layers just described, the ‘composite margin’ of what each

purchases (reflecting net prices to the customer) and its ‘costs-to-serve.’ The

exhibit debunks the myth that companies with the highest sales must also

generate the highest profits.

Note that migrating customers to the upper-left corner is equivalent to moving

individual data points in the profit profile in Exhibit 30.3 from right to left

and bottom – to top. Knowing where customers are located on the matrix requires

ABC data.

Exhibit 5. Migrating Customers to Higher Profitability

Segmenting customers with ABC requires some different filters that we will

discuss next.

Options to Raise the Profit Cliff Curve

What does a commercial organization do with the customer profit information? In

other words, what actions can an organization take to increase its profits? This

is all about the ‘M’ in activity-based management (ABM), the managing of costs

and profits. Some customers may be located so deep in the lower-right corner of

the customer profitability matrix that the company will conclude that it is

impractical to achieve profitability with them and they should be terminated.

After all, the goal of a business is not to improve customer satisfaction at any

cost, but rather to attempt to manage customer relationships in order to improve

long-term corporate profitability.

The objective is to make all customers more profitable, represented by driving

them to the upper-left corner. Although this is a partial list, making customers

more profitable can be accomplished by:

- Manage each customer’s costs-to-serve to a lower level

- Establish a surcharge for or re-price expensive cost-to-serve activities

Reduce services

- Introduce new products and service lines

- Raise prices

- Abandon products, services, or customers

- Improve the process

- Offer the customer profit-positive service level options

- Increase costs on activities that a customer shows a preference for

- Shift the customer’s purchase mix toward richer, higher-margin products

and service lines

- Discount to gain more volume with low cost-to-serve customers

Before doing anything and acting hastily, it is important for anyone

interpreting the profit distribution diagram to understand the following key

issues about the diagram:

- This snapshot view of a time period’s cost does not reflect the life-cycle

costs of the products, service lines, or customers that have consumed the

resource and activity costs for that particular time span.

- The information represented in the graph should not be prematurely or

spontaneously acted on. Analysts must appreciate the large difference

between what information is and what making an actionable decision is. They

are not the same.

The important point is that ABC provides fact-based data from which

discovery and questions can be asked. Always remember this: In the absence

of facts, anyone’s opinion is a good one. And usually the biggest opinion

wins! This includes the opinion of your boss or of your boss’ boss. So, to

the degree senior managers are making decisions based on intuition, gut

feel, misleading information or politics, then your organization is exposed

to the risk of poor decisions.

Computer Technology Enables Customer Profitability Reporting

A revolution has occurred in computer technology that allows large-scale and

detailed profitability reporting. In the past, achieving ever-higher levels

of cost accuracy were simply not justified given the extra work involved.

But today, applying computer technology converts that administrative effort

to near zero (after the automated cost system is initially designed and

configured). Further, data storage capacity is now economical.

The attraction of effective costing system is that it can economically scale

to accommodate billions of transactions, access data from diverse multiple

source systems, and be deployed for remote Web-enabled analysis. It reports

validly calculated profits on a moment’s notice rather than two weeks after

a month has ended. As a bonus, with projected sales volume and mix, it

enables reliable what-if scenarios for test-and-learn as well as pro forma

profit-and-loss forecasts.

Profitability reporting at a detailed level gives a meaningful business

context to the realm of business intelligence (BI). In the end, managerial

accounting is just data. It is to be used as a means to an end – namely

decision making. The quality and accuracy of managerial accounting data is

therefore critical.

Because most businesses today have automated transaction and production

systems, the data that costing error is sensitive to is already accurately

captured. 1This means customer profitability information can be instantly

reported at any time on demand. This provides robust information for

customer profit analysis.

Future competitive differentiation will be based on the rate of speed at

which organizations learn, not just the amount they learn. Having all this

revenue, cost and profit margin data is only a beginning. People have to act

on and make decisions with the data.

Coming to Grips with Reality

The CFO can and should work more closely with the marketing and sales

functions to measure and report the nonfinancial balanced scorecard key

performance indicators (KPIs) that impact or reflect the customers’ total

experience and satisfaction. Progressive CFOs understand how customer

experience drivers achieve strategic objectives and indirectly influence

financial results.

Increasingly more organizations are coming to this realization of flawed or

dysfunctional cost reporting, however, they are intimidated by the perceived

tall heights that they would need to scale to return to the levels of cost

accuracy once enjoyed when output diversity was narrow and overhead expenses

were small. Inevitably they come to grip with their predicament. Should they

reform their managerial accounting method using ABC principles and lean

accounting techniques? Or should they take no action and remain with the

status quo hoping that the lack of transparency of indirect costs, their

drivers, and the degree of misleading information will not too adversely

result in bad decision making. In either case, they are both a choice the

accountants are making. That is, to change or not to change–both are

choices, where either option could be inappropriate.

1For advanced systems, there are extraction, transform, and load (ETL) tools

that are applied for input data cleansing to assure higher accuracy of the

calculated and reported information.

This article is an excerpt from Gary Cokins’ book: Performance Management:

Integrating Strategy Execution, Methodologies, Risk Management, and

Analytics; ISBN 978-0-470-44998-1; John Wiley and Sons (2009). Reprinted

with permission.

Gary Cokins, CPIM, is Global Product Marketing Manager of

Performance Management Solutions with SAS, a global leader in business analytics

and performance management software. He is an internationally recognized expert,

speaker and author in advanced cost management and performance improvement

systems. After earning an Industrial Engineering degree from Cornell University

in 1971 and an MBA from Northwestern University Kellogg Graduate School of

Management, Gary began his career as a Financial Controller and Operations

Manager with FMC Corp. He worked for15 years as a Consultant at Deloitte, KPMG

Peat Marwick and Electronic Data Systems (EDS), where he headed EDS’ Cost

Management Consulting Services. Gary was the lead author of the acclaimed “An

ABC Manager’s Primer” sponsored by the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA).

His “Activity-Based Cost Management: An Executive’s Guide” recently ranked as

the best-selling book of 151 titles on the topic. Gary’s other books include

“Activity-Based Cost Management: Making it Work,” “Activity-Based Cost

Management in Government”, and his latest work, “Performance Management:

Integrating Strategy Execution, Methodologies, Risk, and Analytics.” He has

served on committees of professional societies including CAM-I, AICPA, the

Supply Chain Council, the American Society for Quality (ASQ) and the Institute

of Management Accountants (IMA). Gary is a member of the editorial advisory

board of the Journal of Cost Management. For article feedback, contact Gary at

gary.cokins@sas.com

|